- Radegund

- (c. 525-587)Merovingian queen and abbess, Radegund stands in stark contrast to other famous sixth-century Merovingian queens such as Brunhilde and Fredegund, who were known for their bloody quest for power and defense of family interests. Unlike them, Radegund renounced the worldly life and rejected an earthly family for a heavenly one. Although married to a Merovingian king, she lived a celibate life and was eventually allowed to leave her husband and found a convent. Her community, in which Radegund accepted a lowly position rather than that of abbess, was well known for its piety, but also for its internal turmoil, brought on by the competition between noble and non-noble members of the convent. Even though she renounced the world, Radegund did not remain completely separate from it, corresponding with bishops, kings, and emperors. She was held in such great esteem by her contemporaries that they wrote two biographies of her, and the sixth-century historian Gregory of Tours included much information about her in his History of the Franks, as well as the letter of the foundation of her monastery.Born to the royal family of the barbarian kingdom of Thuringia in about 525, Radegund was brought into the Merovingian kingdom in 531 when the sons of the first Merovingian king, Clovis, Theuderic I (r. 511-533) and Chlotar I (r. 511-561), destroyed her family's kingdom. Radegund herself described the destruction of the kingdom in an epic poem she wrote, which reveals her sadness over the kingdom's fate and the death of her brother, who was killed by Chlotar sometime after he captured the brother and sister and took them back to his kingdom. Although he already had at least one wife and as many as seven, Chlotar married Radegund in 540 in order to legitimize his authority in Thuringia. According to one of her biographers, the sixth-century poet Venantius Fortunatus, who was her chaplain, Radegund spent her youth in preparation for her eventual marriage and was well educated, studying the works of St. Augustine of Hippo, St. Jerome, and Pope Gregory the Great, among others. During her marriage to Chlotar, Radegund remained celibate, much to her husband's dismay, but was able to exploit her position for the benefit of others nonetheless. She actively sought to free captives, often paying the ransoms for their release. She also spent lavishly on the poor.Her marriage to Chlotar, however, was clearly not meant to last, and in about 550 she left him to found the monastery of the Holy Cross in Poitiers. The accounts of her separation from her husband are contradictory. According to Venantius Fortunatus, Radegund was allowed to leave her husband because of the murder of her brother. Chlotar, after killing her brother, not only allowed the separation but sent her to the bishop of Soissons, who was to consecrate her in the religious life in order to calm the situation politically with the bishops of his own kingdom. Her other biographer and disciple, Baudonivia, writing in the early seventh century, portrayed the whole affair differently. She wrote that after Radegund had left the king, Chlotar fell into a fit of despair and desired that his wife return to him. Indeed, he even went to Poitiers with one of his sons, Sigebert, to take his wife back, but relented in the end and allowed her to take up the religious life. This decision was influenced by Radegund's connections with numerous bishops of the kingdom, who helped persuade Chlotar to allow her to live as a nun. Moreover, not only did Chlotar allow her to take the veil but he also provided a substantial endowment so that she could establish her new community in Poitiers.Although the founder of the new religious community, Radegund was not its abbess. As noted in the letter of foundation, preserved by Gregory of Tours, Radegund appointed Lady Agnes as mother superior. Radegund writes, "I submitted myself to her in regular obedience to her authority, after God" (535). Indeed, despite her royal standing, Radegund lived her life at the monastery of the Holy Cross as a regular nun and set the example in pious living for the other nuns in the community to follow. Baudonivia wrote in her biography that Radegund "did not impose a chore unless she had performed it first herself"(Thiébaux 1994, 113). She was also zealous in the performance of her religious duties and was frequently at prayer. Even while resting, Radegund had someone read passages from the Scriptures to her. She also performed acts of extreme self-mortification, and, according to Venantius Fortunatus, sealed herself up in a wall in her monastery near the end of her life and lived there as a hermit until her death.Radegund lived her life as a simple nun in her community, but she was still royalty; she continued to participate in the life of the kingdom and used her status for the benefit of the community she established. In her foundation letter, she secured the protection of her monastery from the leading bishops of the realm as well as from various Merovingian kings. She also cultivated her relationship with the bishops of the realm, including her biographer, Venantius Fortunatus, and Gregory of Tours, after the initial contacts at the foundation. Her royal status enabled her to acquire a piece of the True Cross (believed to be the cross on which Christ was crucified) from the emperor in Constantinople. This act, which benefited her community, may also have had political overtones. Her correspondence with the emperor and his delivery of the holy relic may have been intended to improve diplomatic ties between the Merovingian dynasty and Byzantine emperors. She also prayed for the various Merovingian kings and often sent them letters of advice, partly in an effort to preserve the peace within the Merovingian kingdom. She also prohibited the marriage of a Merovingian princess, a nun at the convent in Poitiers, to the Visigothic prince Reccared. Indeed, even though she lived the life of a simple nun, Radegund played an important role in the kingdom because of her status as a former Merovingian queen.

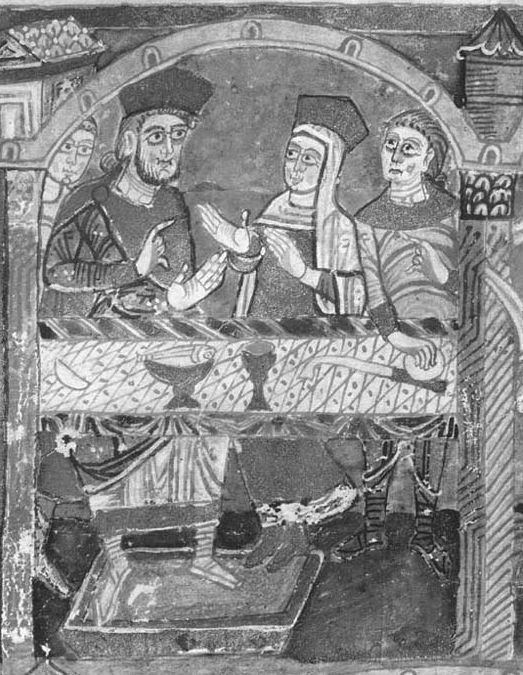

Radegund and King Chlotar (The Art Archive/Bibiothèque Municipale Poitiers/Dagli Orti)See alsoAugustine of Hippo, St.; Brunhilde; Fredegund; Gregory of Tours; Gregory the Great, Pope; Merovingian Dynasty; Monasticism; Reccared I; Visigoths; WomenBibliography♦ Gregory of Tours. The History of the Franks. Trans. Lewis Thorpe. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1974.♦ Schulenburg, Jane Tibbetts. Forgetful of Their Sex: Female Sanctity and Society, ca. 500-1100. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.♦ Thiébaux, Marcelle, trans. The Writings of Medieval Women: An Anthology. New York: Garland, 1994.♦ Wemple, Suzanne. Women in Frankish Society: Marriage and the Cloister, 500-900. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985.♦ Wood, Ian. The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450-751. London: Longman, 1994.

Radegund and King Chlotar (The Art Archive/Bibiothèque Municipale Poitiers/Dagli Orti)See alsoAugustine of Hippo, St.; Brunhilde; Fredegund; Gregory of Tours; Gregory the Great, Pope; Merovingian Dynasty; Monasticism; Reccared I; Visigoths; WomenBibliography♦ Gregory of Tours. The History of the Franks. Trans. Lewis Thorpe. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1974.♦ Schulenburg, Jane Tibbetts. Forgetful of Their Sex: Female Sanctity and Society, ca. 500-1100. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.♦ Thiébaux, Marcelle, trans. The Writings of Medieval Women: An Anthology. New York: Garland, 1994.♦ Wemple, Suzanne. Women in Frankish Society: Marriage and the Cloister, 500-900. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985.♦ Wood, Ian. The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450-751. London: Longman, 1994.

Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe. 2014.